Even when the risks are abundantly clear. Even when a loved one appears unchanged from the outside looking in. Even with years of group meetings and one-on-one counseling. Even when the battle through addiction becomes a matter of life and death — losing still happens.

Dealing with the unkind prospect of losing a peer, co-worker, or loved one to addiction summons a nearly impossible amount of vulnerability and time. Occupying one of these roles for an individual in recovery infers a naive sort of optimism. Of course, they will kick the habit once and for all, because the alternative is nearly unthinkable. So when the unthinkable happens, how do we cope?

THE PROJECTION OF COMPLACENCY

Most addicted individuals know two versions of their own self: the person they project around others, and the person they are when truly alone. Connecting to this outward-facing persona functions as a default buffer to mitigate interpersonal communication. The nature of use disorder engulfs individuals coping with addiction with a nearly incommunicable sense of shame — one that only thrives in the solitude that defines so much of early substance abuse. An abundance of coping individuals eventually find refuge under a separately insidious cultural obsession: work.

Given the emphasis on productivity throughout so much of adult life, it is not all too surprising that those who experience addictive tendencies easily pivot to the overwhelming routine of overworking themselves until they are too tired to feel the tempting pull of alcohol and/or substances by the end of the day. While substituting the mental toll of all-consuming work for that of use disorder might alleviate some of the physical and mental repercussions, merely replacing one behavioral addiction for another denies the presence of underlying disorder. In this regard, losing oneself within the labors of a job resembles a doctor treating a symptom as opposed to the condition.

The widespread acknowledgment of work presenting a struggle in daily life can also act as a deterrent to any concerns surrounding a friend, colleague, or loved one battling addiction. Even if someone is really in the throes of a particularly challenging step in their recovery, passing off this tribulation as an extension of struggling through professional challenges presents a safety net for anyone who struggles with sobriety to avoid sharing their truth. So many conversations about use disorder end with someone saying “I am working on it,” allowing both parties to feel complacent.

THE GUILT SURROUNDING IRRATIONALITY

Should you ever experience the loss of someone to use disorder, the strange degree of guilt surrounding the circumstance of overdose is steeped in irrationalities, all of which directly result from the incomprehensible nature of addiction. Attempting to apply logic to mental health disorders is like trying to fit an airplane under a microscope, but we do it nonetheless. Still, the urge to wrap the mind around the amorphous shape of addiction keeps us up at night, begging the question: what more could we have done?

The undercurrent of guilt manifests through a multitude of emotions. Anger, grief, relief, depression — all can provide avenues for the unrequited sense of shame experienced from comprehending the fallout of losing someone to addiction. Blame tends to be misdirected to any number of channels: others, oneself, the individual born into addiction. Understanding may never come from the loss of troubled souls, and we must accept that any semblance of closure may continue to evade those within the proximity of addiction forever.

WHAT DOES “MOVING ON” EVEN MEAN THEN?

If understanding the guilt steeped in loss proves impossible, then this hanging inevitability might feel daunting to face head-on. Keep in mind that there are many others who have been through the exact same experience. Speaking with those who can identify with this lack of closure often provides the next best recourse. Many benefit from talking through their shared experiences during group meetings with Al-Anon or other recovery-based organizations. Setting aside time to dedicate to your mental health might not alleviate all the struggles involved in losing a battle to addiction, but it can help to feel heard.

The concept of moving on or attaining the all-elusive sense of catharsis might appear from the outside to be the missing piece for emotional wellness. In reality, chasing this unattainable mindset might be the anchor that is holding people back when they hurt most. Taking strides to make peace through the gradual, redemptive work of forgiving yourself — for yourself — with the assistance of trained professionals stands to effect the greatest degree of change.

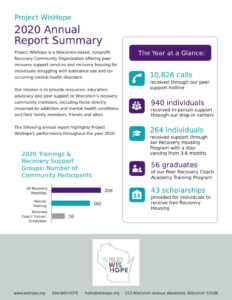

Loss clouds the deeply entrenched irrationality of addiction, mortality and all. The mental gymnastics of comprehending the inner functions of destructive use disorder take a toll on mental well-being. Anyone in the periphery of this mental health condition stands to benefit from counseling and group meetings, where individuals can share and identify with the repercussions of losing a loved one to use disorder. Nothing about loss is easy, but finding people who have experienced the same grief shouldn’t be the step holding anyone back from processing their emotional response. Take the steps forward today to position yourself with resources to heal from potential trauma. At WisHope, we understand that the road to recovery is a life-lasting pursuit, and we aim to provide you the tools and resources to do this, long after your stay at our treatment facilities or recovery homes. Don’t wait to get help — call us today at (844) 947-4673.